I would just like to preface this; the title of the game is still a work in progress. So without further ado, here is a rundown of the development of my game, Festivities!

Theme

The theme of Festivities is building a festival line-up, using international and familiar Australian acts, to sell the most tickets, while traversing obstacles and competitors.

Setting

Amidst the current uncertainty of the Australian music festival industry, punters (attendees) are feeling worried if they’ll even be able to enjoy music festivals in the future. The setting of being in present Australian times, allows for players to fantasise what the line-ups on table would be like as an actual music festival, fostering a sense of competition amongst players and anticipatory nostalgia, reimaging the future rather than the past (Bergs et al. 2020).

Genre and Industry Segment

The genre of Festivities slots into the family game genre, targeted towards young Australian adults. Being a simple structured card game, allows for autonomy in how the experience and strategy is approached. It also draws from the licensed games category using real world music artists to build a foundation of familiarity with the players.

Key Game Mechanics

Cards and actions are two key game mechanics of Festivities. The game hosts two separate decks, one holding ‘artists’ and the other holding actions. The artist cards are what’s used to construct a players’ line-up, and action cards can be used to further aid the construction of a line-up or disrupt the flow of play.

Alongside these mechanics, turns plays a vital role to keep re-direct flow when disrupted. The dealing of the cards also utilises an asymmetry mechanic, creating an unpredictability in play (Moore 2020). Despite the notion that there may be too many mechanics incorporated for a simple game, all together provide a balanced compromised for an enjoyable experience (Forbeck 2011).

Core Game Loop

Festivities is a card game of players using actions and strategy to collect high scoring artist cards to hold the biggest music festival.

World-Building

Using Marie-Laure Ryan’s approach of ‘Ontological Rules’ (2018), I was able to assign alethic values to the options of the in-development world.

| World Options | Alethic Value |

| Inventory of individuals | Same – using real world artists that players may be already familiar with. |

| Property of common individuals | Same (Verified) – the characters used are real world individuals/groups. |

| Natural species | Same – although doesn’t necessarily apply due to the absence of creatures besides humans. |

| Kinds of natural (physical) laws | Same – the fundamental laws of reality are still in place, stripped of complexity. |

| Technology | Same – realistic approach. |

| Cosmology | One world. |

| Time | Historical – or more so altering the players present e.g. using present examples of artists in unique groupings perhaps not seen before in existing festivals. |

| Space/Geography | Augmented – Players may choose to communicate the details of their festival but there is no set space as to where it must be. There is influence on the notion that it’s an Australian locale with most artist cards being Australian. |

| Logic | Occasionally violated – vastly different artists can be on one player’s line-up. Compared to the realistic economics of building a music festival, Festivities is a severely simplified practice of doing so. |

Although the assigned alethic values may be too akin to the real world to be exciting and immersive, I found quite the opposite to be evident after an initial play test. Participants were excited to chase after their favourite artists other players possessed and to grow their line-ups to higher totals. This approach allowed me to create a world that is familiar and therefore accessible to a range of players (Moore 2022), whether they were a participant of the Australian festival world or not.

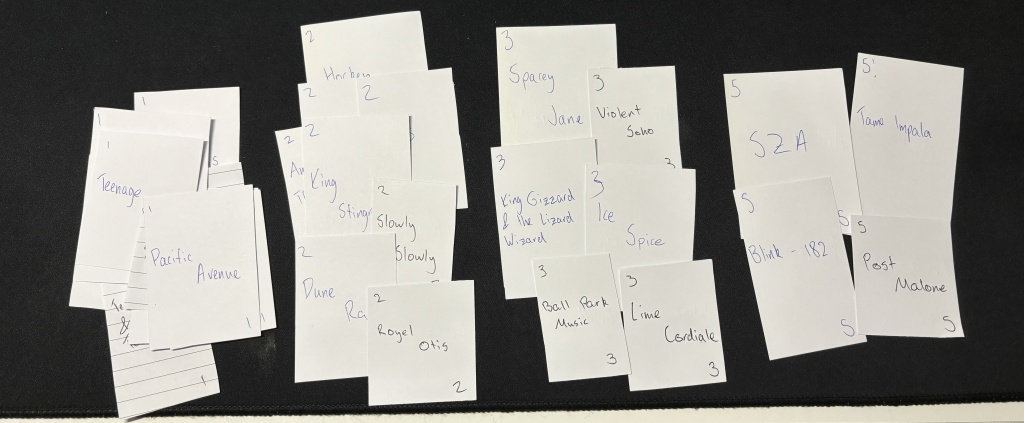

Developed Materials

I’ve developed two decks of cards, actions, and artists. The artist cards all have a number in the top and bottom corners, inspiration drawn from UNO and traditional playing cards. These numbers signify the number of ‘tickets’ sold, with the person holding the highest sum of their 5 cards winning the game. As for the action cards, I’ve developed 9 types of action cards, all of different rarity.

Prior to prototyping, I wanted to include a token aspect to the game to signify the ‘tickets’ a player had sold. Once development began, the addition wasn’t necessary as this could be indicated with the numbers on the cards bearing this role fully.

Three-Act Structure

First Act

The first act begins with the set-up of play, and the reading and understanding of the rules. All players are dealt 1 artist card each at the start of the game alongside their 5 action cards. The player who last attended a music festival will begin play.

Second Act

Play proceeds in a round-table motion, at the beginning of a turn, the player will pick-up an action card, then may choose to play an action card or pass. This is where competition begins to increase, with artist cards being stolen, valuable cards are drawn, and opportunities may prevail for players to trade what appears to be the leading position (Tidball 2017). Players must solve the puzzle of how to garner the best artist cards using only the card they’ve been dealt.

Third Act

Once all players have their 5 artist slots filled the game is over, scores are tallied and the player with the highest is declared the winner.

Playtesting

Following an insightful playtest with 3 players, I gathered plenty of meaningful feedback. The group suggested to re-evaluate the amount of certain card types in the deck, adding more artists and altering the points system, and more. This feedback is going to help me head in a positive direction of development. The participants also really enjoyed the game, found the rules were easy to learn, and I observed multiple emotionally satisfying moments from the participants. Overall, I’m very satisfied with where this development is headed, and am keen to do more with this project.

References

Feature image created by Midjourney using prompt: design a box for a card game about building a music festival –ar 16:9

Bergs, Y, Mitas, O, Smit, B & Nawijn, J 2020, “Anticipatory nostalgia in experience design,” Current issues in tourism, vol. 23, no. 22, pp. 2798–2810.

Forbeck Matt 2011. Metaphor vs. Mechanic: Don’t Fight the Fusion. The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design (edited by Mike Selinker). Open Design LLC Kirkland, WA.

Moore C, 2022, ‘A practical method for world building.’ lecture, BCM 300, University of Wollongong, viewed 3rd May 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEcCT3isM9w.

Moore C, 2020, ‘Game Mechanics: a primer for experience design.’ lecture, BCM 300, University of Wollongong, viewed 3rd May 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bB_UAFwd4OQ.

Ryan, Marie-Laure 2018. ‘Ontological Rules’ The Routledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds, (Mark J.P. Wolf ed), Routledge New York.

Tidball, Jeff (2017) Pacing Gameplay: Three-act Structure Just Like God and Aristotle Intended, The White Box Essays. Gameplaywright, Minnesota.

Leave a comment